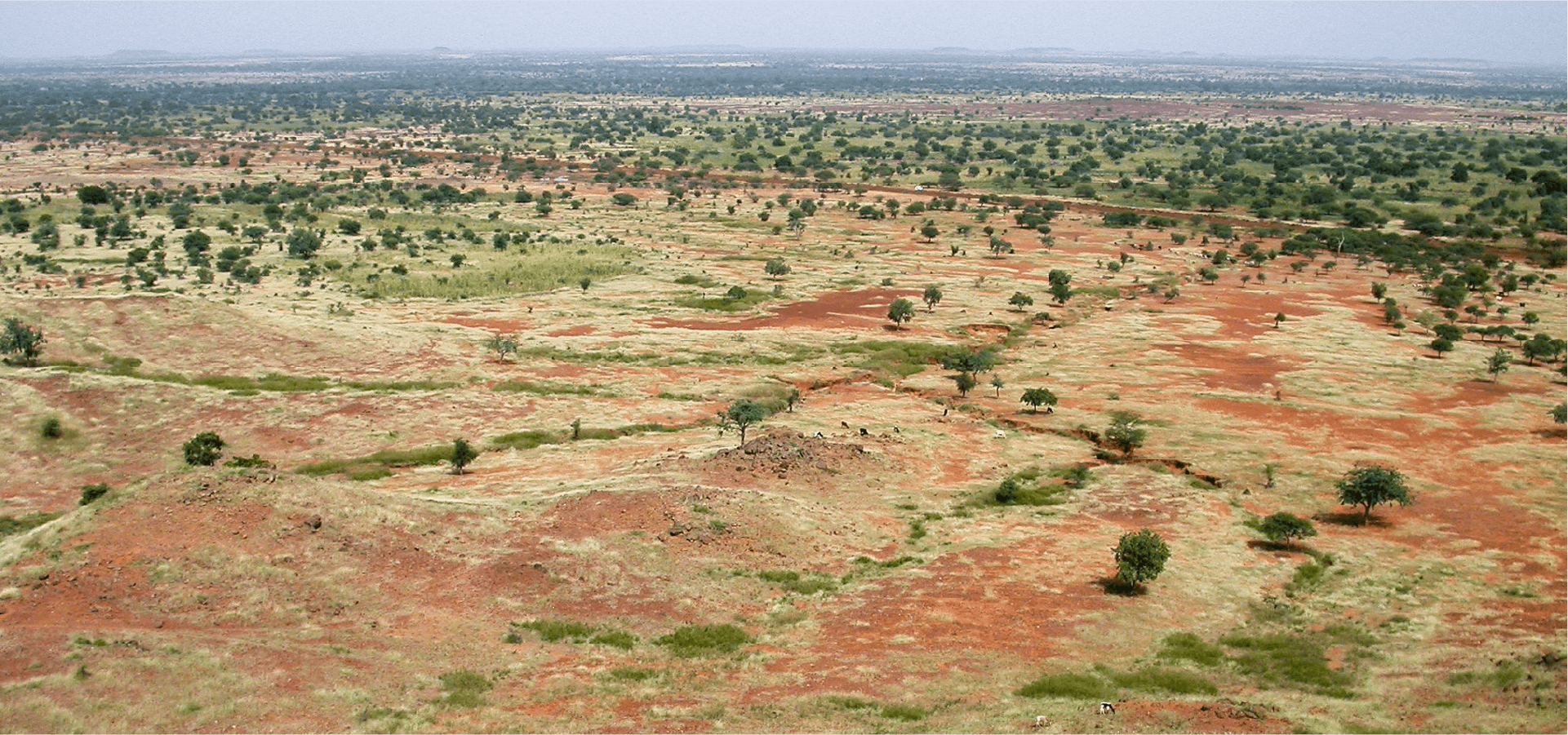

Between 80% and 90% of people in the Sahel are farmers or pastoralists.[1] Yet despite decades of investment in rural development, their incomes are among the world’s lowest and their livelihoods are threatened by climate change. Widespread food insecurity and rising outmigration have accelerated land degradation and led to the spread of insurgencies across several countries.

But lessons have been learned. Now we know how to fix this.

The Sahel Mosaic aims to prime the pump of economic development by creating green jobs, improving livelihoods, and strengthening resilience to climate change through the large-scale restoration of degraded agroecosystems. Our vision is to co-develop up to 100 regenerating landscapes of up to 100,000 ha each, called Special Regeneration Zones, through a community-centric approach to land management. These combine the governance systems, technical knowledge and community vision needed to restore degraded ecosystems. Beyond simply boosting incomes, these zones can give farmers and pastoralists the ability to invest in their future – and the stability to attract external investors.

Now is the time to invest in the Sahel’s potential, as momentum builds under the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration and initiatives like the Great Green Wall. Join us in our vision of a Sahel Mosaic, in which rural communities invest in their own future and fundamentally transform the region.

Mr Ndiaye’s trees

During Senegal’s dry season, the young trees dotting El Hadj Ndiaye’s fields often prove too much of a temptation for herders searching for fodder or women for firewood – so he and his sons will sometimes guard them throughout the night. To Mr Ndiaye, who nurtured dormant seeds and shoots to regenerate his land, the trees provide fuel and fodder, higher millet yields and protection from soil erosion. They represent better food security for him and his family in increasingly uncertain times. Protecting the trees is an ongoing struggle, but well worth it in his eyes.

Mr Ndiaye’s trees are just a microcosm of the enormous restoration potential of the Sahelian landscape, where large-scale regeneration – often led by farmers or herders – is enabling the regrowth of dozens of species of native trees and the useful plants they shelter,[2] all while sequestering valuable carbon that could generate income for landholders.

Read story »