Trees do many things for cities, and the potential for change led by urban forestry is huge, according to Cornell and Yale university fellows who spoke at an event in Nairobi.

By Cathy Watson

Recently, the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF) held its first-ever science talk on urban forestry, the practice of cultivating trees and green spaces within cities for environmental, social and economic benefits.

“Trees in cities in relation to adaptation and mitigation are very important,” said Vincent Gitz, CIFOR-ICRAF’s director of programme and platforms. “We can develop an agenda on the role of trees in cities that is as strong as the agenda we have for forests and trees in agriculture.”

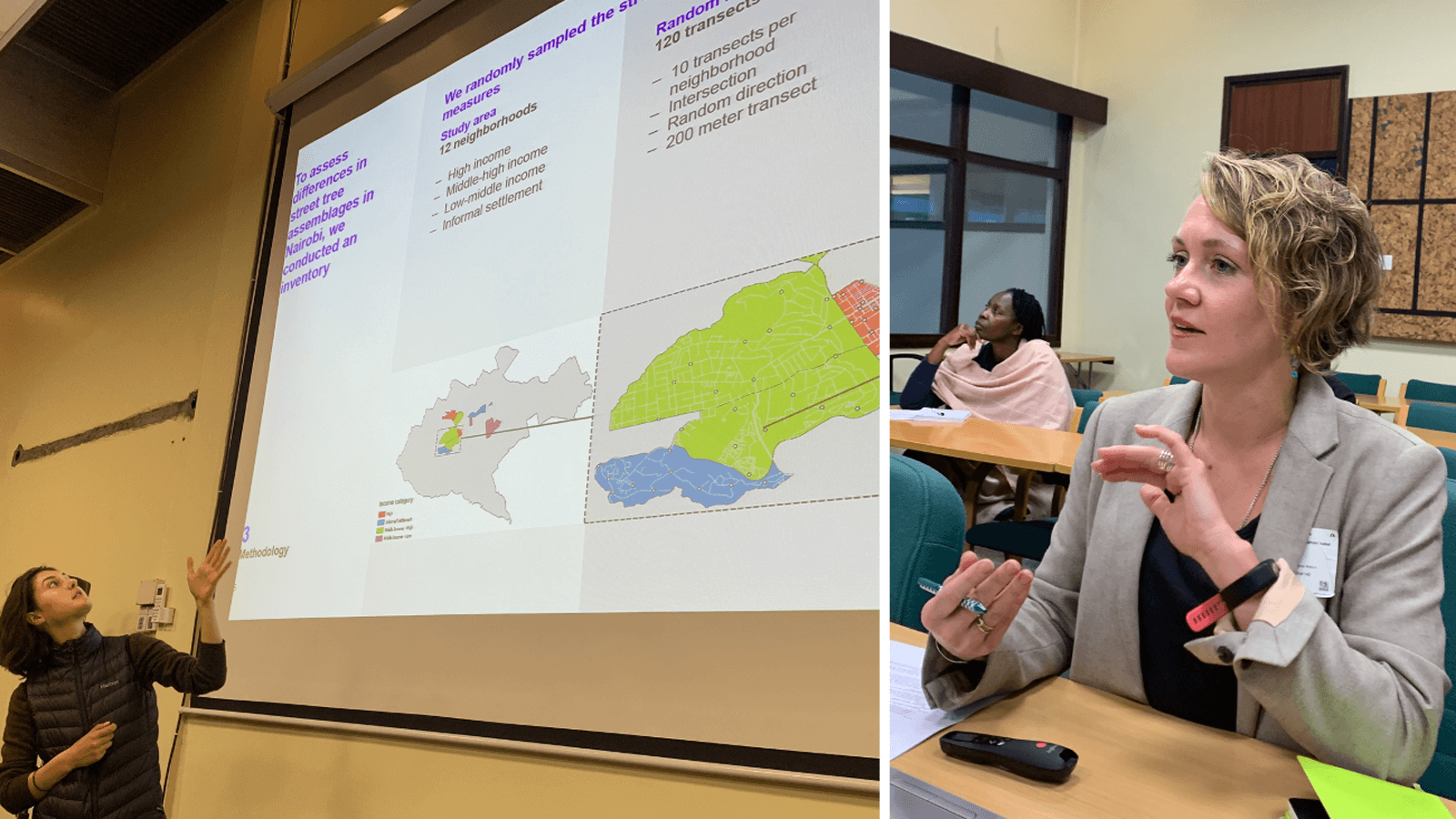

The speakers included urban forestry research fellows at CIFOR-ICRAF, namely Alice Gerow, who is pursuing a master’s in forestry at the Yale School of the Environment, and Kate Chesebrough, a professional landscape architect who is studying for a master’s degree at Cornell University’s Department of Landscape Architecture.

Gerow shared some early observations from her field inventory of Nairobi’s street trees. Her census asks how the abundance, size structure and species composition of street tree assemblages differ across neighbourhoods along a socio-economic gradient.

So far, in 90 locations, she has found over 1,500 street trees and treelike monocots of approximately 130 species. Confirming what many botanists suspected, three-quarters of the species do not naturally occur in Kenya, and five exotic tree species account for more than a quarter of the trees, among them Brazil’s Jacaranda mimosifolia; Howea forsteriana, a palm from an island in the Tasman Sea; and Filicium decipiens, a native of India’s Western Ghats mountain range and Sri Lanka.

“Diversity of species composition is key to the resilience of urban forests. Awareness raising is needed if Nairobi is to maintain the benefits of street trees over time,” said Gerow, who also noted the paucity of indigenous trees. One participant also observed that “indigenous trees host more birds than exotics do.”

Partly bearing out her hypothesis that lower-income neighbourhoods will have lower tree density and different species composition, Gerow found that in high-income areas, 100 percent of her transects – lines used for measurement between two points – had trees, with an average of more than 30 trees every 200 metres. This was approximately 15 times more than what she found in low-income and informal settlements.

“It is easier to address inequity in access to green infrastructure by planting a street tree than creating a park,” said Gerow, who has also worked for parks departments in Paris and New York. “Street trees are key pillars of an urban forest that benefits all residents. Goodwill towards street trees could lead Nairobi to be a model.”

Chesebrough spoke about landscape architectural design thinking for a robust urban forest at large and small scales over time. Her ultimate goal is to support urban forestry in Nairobi with informed and actionable takeaways.

The Cornell master’s student called for the availability of seedlings from a palette of native urban-adapted trees and defined urban forestry as the “entire network of trees within an urbanized context: individual and community, ecological corridors, patches and nodes.”

“Urban forestry is therefore networked – created and performed differently depending on actors and conditions,” she said.

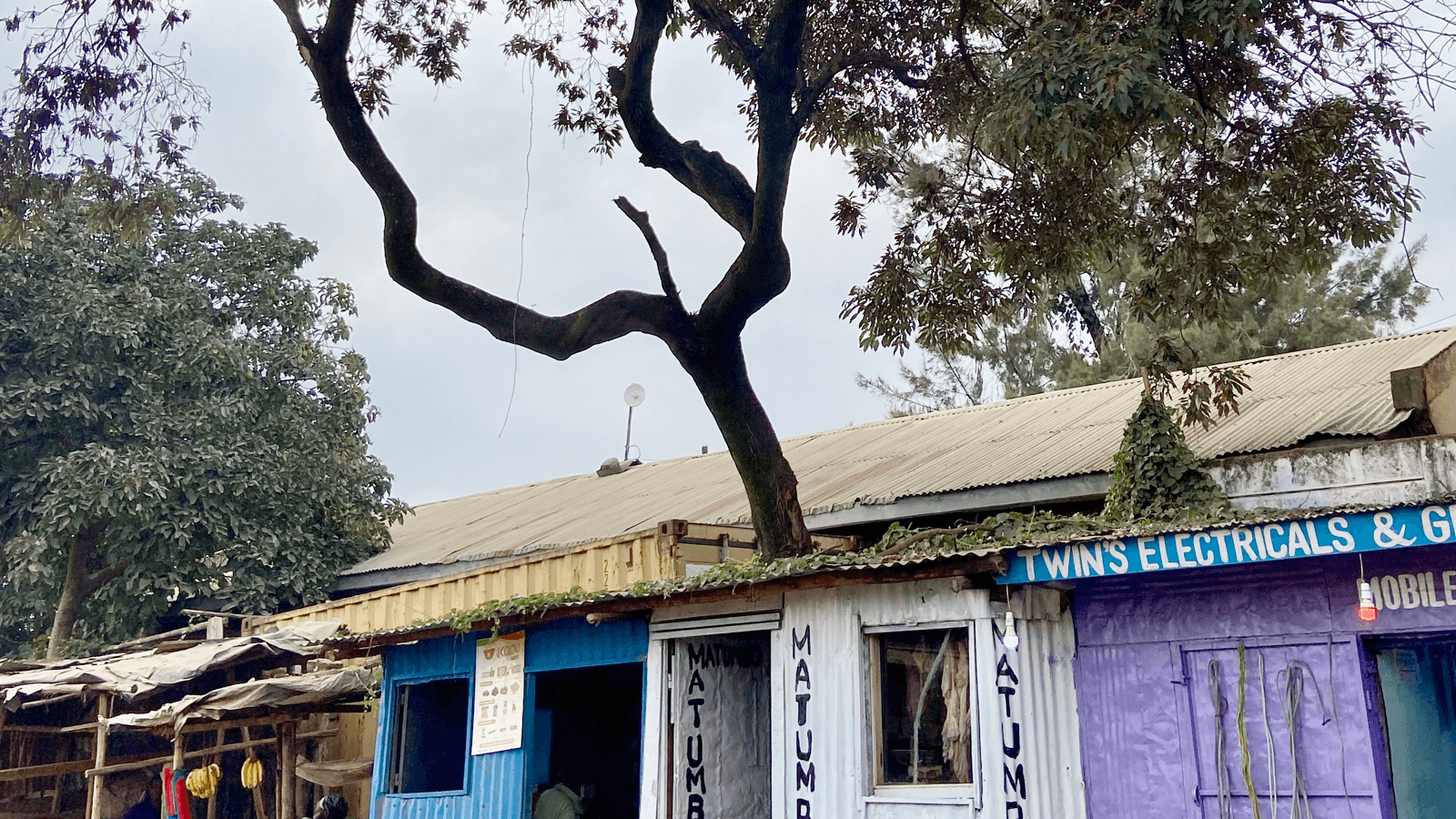

Conducting research largely on trees in informal settlements, Chesebrough stressed the importance of maintenance: “Trees are about time, and urban forestry is about adopting and growing trees, not simply planting. Workers are an integral part of this. Maintenance must be considered in budgets.”

The care and management of urban trees strongly affect perceived safety, according to Chesebrough. Nairobi slum dwellers associate “bushy” and overgrown vegetation with crime, echoing the crime-related hesitancy about trees that Gwedla and Shackleton (2019) found in South African townships, she said.

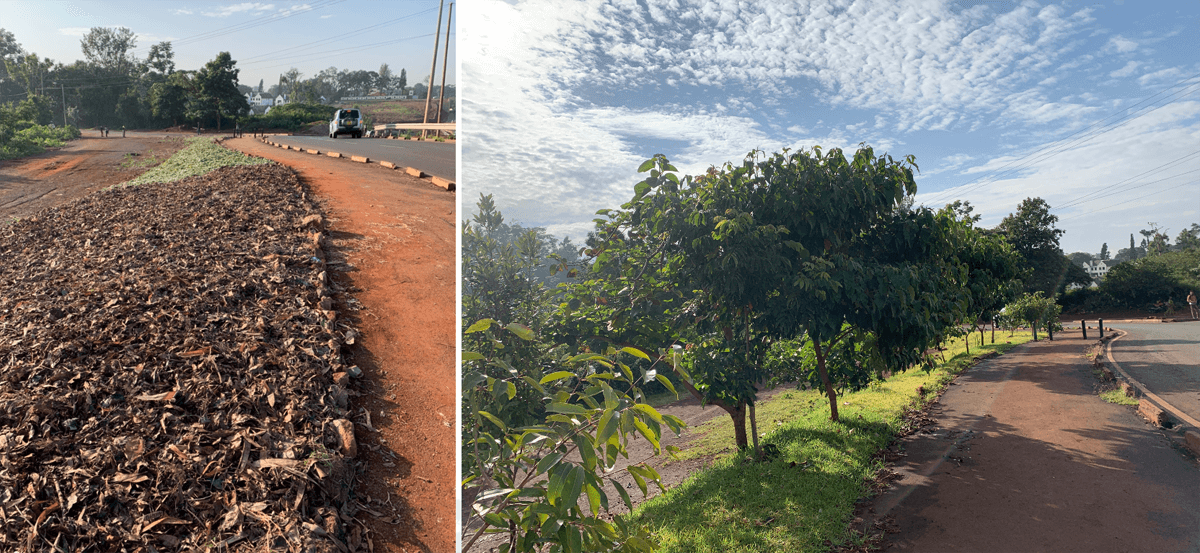

“Urban forestry can do many things for cities, and the potential for change led by urban forestry is huge,” Chesebrough said. She referred to a project by CIFOR-ICRAF staff to restore road reserves in Nairobi, describing it as a “model partnership for roadside forests” and a “linear public space,” as defined in the 2020 UN-Habitat Nairobi City County: Public Space Inventory and Assessment.

“The planet is warming up, and people living in big cities are highly affected,” said Ann Degrande, CIFOR-ICRAF’s coordinator in Cameroon. “Studying the presence of urban trees and understanding people’s perceptions are extremely relevant. Finding ways of getting as much green as we can in our cities matters as much as trees in rural landscapes.”

“In government, we do not have this background,” said Lawrence Wachira, an environment manager at the Kenya Urban Roads Authority. “We are struggling with expertise. A road engineer may have to act as landscape architect, and you end up doing very little urban forestry. But we have road reserves amounting to 7,000 hectares that we need to plant.”

It sounded like an invitation.

“We are entirely committed to urban forestry,” says Éliane Ubalijoro, chief executive officer of CIFOR-ICRAF. “The abrupt dichotomy between rural and urban is no more. We address all ecosystems where there are trees. Trees in urban landscapes combat heat islands, bring flood resilience and are critical contributors to livable cities.”

For more information, please contact Cathy Watson at c.watson@cifor-icraf.org.

Further background and tools:

- CIFOR-ICRAF’s TreesAdapt Platform is designed to support all actors, including those in cities, to use to tree for their solutions to adapt to climate change.

- CIFOR-ICRAF’s Regreening App is ideal for urban foresters to map polygons and tag, label and record important attributes of individual street trees such as height, DBH and species.

- UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s Guidelines on urban and peri-urban forestry. FAO Forestry Papers No. 178.

- Reuters editorial: “Nairobi recovers its green spaces during pandemic. Other cities can too”.

- In US cities, American Forests leads thinking to address inequity in tree cover. See https://www.americanforests.org/our-programs/tree-equity/