CIFOR-ICRAF s’attaque aux défis et aux opportunités locales tout en apportant des solutions aux problèmes mondiaux concernant les forêts, les paysages, les populations et la planète.

Nous fournissons des preuves et des solutions concrètes pour transformer l’utilisation des terres et la production alimentaire : conserver et restaurer les écosystèmes, répondre aux crises mondiales du climat, de la malnutrition, de la biodiversité et de la désertification. En bref, nous améliorons la vie des populations.

GOUVERNANCE

Explore eventos futuros e passados em todo o mundo e online, sejam hospedados pelo CIFOR-ICRAF ou com a participação de nossos pesquisadores.

ÚLTIMAS NOTÍCIAS

A ciência precisa de canais de comunicação claros para cortar o ruído, para que a pesquisa tenha algum impacto. O CIFOR-ICRAF é tão apaixonado por compartilhar nosso conhecimento quanto por gerá-lo.

Découvrez les évènements passés et à venir dans le monde entier et en ligne, qu’ils soient organisés par le CIFOR-ICRAF ou auxquels participent nos chercheurs.

Jelajahi acara-acara mendatang dan yang telah lalu di lintas global dan daring, baik itu diselenggarakan oleh CIFOR-ICRAF atau dihadiri para peneliti kami.

Actualités

Pour que la recherche ait un impact, la science a besoin de canaux de communication clairs pour aller droit au but. CIFOR-ICRAF est aussi passionné par le partage de ses connaissances que par leur production.

ÚLTIMAS NOTICIAS

Para que la investigación pueda generar algún impacto, los conocimientos científicos requieren de canales de comunicación claros. En CIFOR-ICRAF, compartir nuestros conocimientos nos apasiona tanto como generarlos.

Explore eventos futuros y pasados organizados por CIFOR-ICRAF o con la participación de nuestros investigadores.

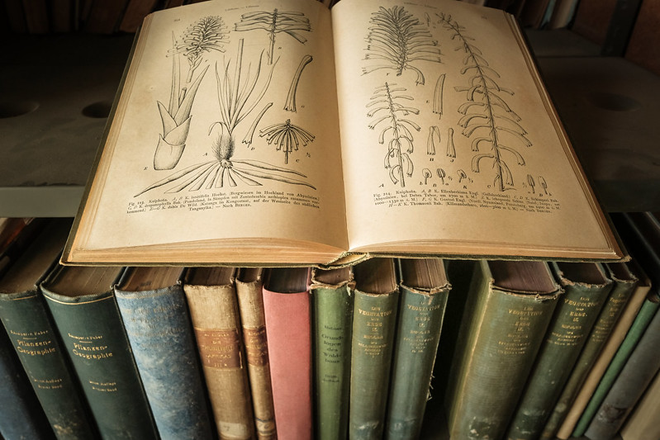

CIFOR-ICRAF publie chaque année plus de 750 publications sur l’agroforesterie, les forêts et le changement climatique, la restauration des paysages, les droits, la politique forestière et bien d’autres sujets encore, et ce dans plusieurs langues. .

DÉCOUVRIR NOS RESSOURCES

Parcourez les recherches publiées par le CIFOR-ICRAF dans plusieurs formats, tous disponibles gratuitement en ligne.

Kabar terbaru

Ilmu pengetahuan membutuhkan saluran komunikasi yang jelas untuk mencapai tujuan, jika ingin dampaknya terlihat. CIFOR-ICRAF sangat bersemangat untuk berbagi pengetahuan sembari menghasilkan pengetahuan itu sendiri.

CIFOR-ICRAF a un impact fondé sur la science. Nous menons des recherches innovantes, renforçons les capacités de nos partenaires et engageons activement le dialogue avec toutes les parties prenantes, en apportant les dernières connaissances sur les forêts, les arbres, les paysages et les populations à la prise de décision au niveau mondial.

CIFOR-ICRAF s’attaque aux défis et aux opportunités locales tout en apportant des solutions aux problèmes mondiaux concernant les forêts, les paysages, les populations et la planète.

Nous fournissons des preuves et des solutions concrètes pour transformer l’utilisation des terres et la production alimentaire : conserver et restaurer les écosystèmes, répondre aux crises mondiales du climat, de la malnutrition, de la biodiversité et de la désertification. En bref, nous améliorons la vie des populations.

GOUVERNANCE

CIFOR–ICRAF achieves science-driven impact. We conduct innovative research, strengthen partners’ capacity and actively engage in dialogue with all stakeholders, bringing the latest insights on forests, trees, landscapes and people to global decision making.

CIFOR–ICRAF publishes over 750 publications every year on agroforestry, forests and climate change, landscape restoration, rights, forest policy and much more – in multiple languages.

Explore our knowledge

Browse CIFOR–ICRAF’s published research in a wide range of formats, all of which are available for free online.

CIFOR–ICRAF addresses local challenges and opportunities while providing solutions to global problems for forests, landscapes, people and the planet.

We deliver actionable evidence and solutions to transform how land is used and how food is produced: conserving and restoring ecosystems, responding to the global climate, malnutrition, biodiversity and desertification crises. In short, improving people’s lives.

Governance

Autres vidéos qui pourraient vous intéresser

Pour toute demande d’informations, contactez

Le Centre de Recherche Forestière Internationale et le Centre International de recherche en Agroforesterie (CIFOR-ICRAF) exploite le pouvoir des arbres, des forêts et des paysages agroforestiers pour relever les défis mondiaux les plus urgents de notre époque – la perte de la biodiversité, le changement climatique, la sécurité alimentaire, les moyens de subsistance et les inégalités. CIFOR et ICRAF sont des centres de recherche du Groupe Consultatif pour la Recherche Agricole Internationale (CGIAR).

Pour toute demande d’informations, contactez:

Pour toute demande média, contactez :

contenu

- Accueil

- À propos

- Recherches

- Actualités

- Evènements

S’inscrire pour recevoir les dernières actualités du CIFOR-ICRAF

© 2025 Centre de recherche forestière internationale (CIFOR) et Centre International de Recherche en Agroforesterie (ICRAF) | CIFOR-ICRAF sont des centres de recherche du CGIAR | Politique de confidentialité et de protection des données personnelles du CIFOR-ICRAF